|

|

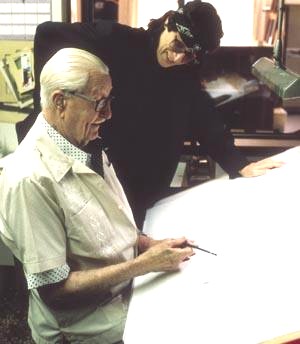

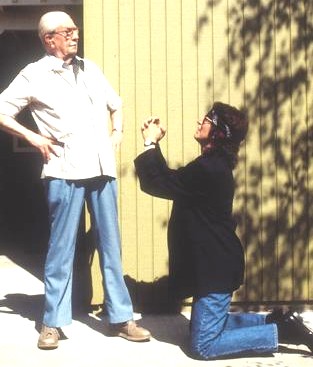

GOTTFRIED HELNWEIN

The Austrian born pop-artist Gottfried Helnwein is well known in Europe for his powerful work in many fields, especially painting and photography. He is also an avid interviewer and author of the book Wer ist Carl Barks? (Who is Carl Barks?).

Helnwein visited Carl Barks in Grants Pass, Oregon, on July 11th, 1992, to produce this interview.

Helnwein: How would you like the

idea of building an actual Duckburg one day?

Barks: Who can tell what Duckburg really looks like?

Helnwein: If one studies your work carefully, there are a lot of

indications. The money bin for example.

Barks: Yeah, the money bin is perhaps the outstanding building in

Duckburg. But I remember one in which the opening panel was a

picture of the ducks up on top of a skyscraper, looking down onto

a busy city with tall, mighty buildings, a wide river and

steamboats.

Helnwein: I remember, yes.

Barks: But that wouldn't be the Duckburg that people should

remember. It would have to be a smaller Duckburg, with Daisy's

and Donald's house in it and a few blocks further Gladstone

Gander's home; and naturally there would have to be Gyro

Gearloose's workshop.

Helnwein: With all his absurd inventions, machines and robots...

Barks: And then up on the hill - the gigantic money bin...

Helnwein: On one side, the Beagle Boys would be drilling a hole

into the exterior walls where the money would roll out. And

inside the money bin, everything would be guarded by traps -

these old cannons, for example, that suddenly pop out of the

ground. I would construct them in such a way that they would

actually function as you walk in.

Helnwein: Since my childhood, I

have dreamed of being allowed to wallow in Uncle Scrooge's coins.

Barks: In Germany they are still printing a lot of these duck

stories, aren't they?

Helnwein: Yes, I think Germany is the greatest market for Donald

Duck comics worldwide. There you'll also find the most fanatical

fans. Have you ever heard of the Donaldists?

Barks: The Donaldists?

Helnwein: It is an association. Or better, an order, which sees

itself as the keeper of the holy grail of the pure and eternal

spirit of Donald. They are conviced that Duckburg actually exists.

Barks: Oh - I remember - I believe I once saw one of their little

pamphlets.

Helnwein: Do you know, by the way, that your stories were

translated into German quite brilliantly by a woman named Erika

Fuchs?

Barks: She must have been very good, because in my conversation

with fans, I always had the impression, that the German readers

best understood my humour, in contrast to the Italians, for

example, where the spirit of my stories apparently was lost in

the translation.

Helnwein: What was the first comic

strip you ever saw in your life?

Barks: Oh, - that was a long time ago, it was in my childhood

around 1906 or 1907.

Helnwein: What was it? Little Nemo?

Barks: Yes, Little Nemo was the first comic that I remember - and

then came Happy Hooligan and others, but I most clearly remember

Windsor McCay's Little Nemo - wonderful drawings.

Helnwein: Did you imagine back then, that you would be drawing

comics yourself?

Barks: I believe so. I always wanted to know how to make

something like this, and I had a great desire to try it myself.

Helnwein: These stories used to appear in the Sunday newspaper in

those days, didn't they?

Barks: Yes, we got the paper around Tuesday. In San Francisco the

paper appeared on Saturday or Sunday, but we up in our home ranch

saw it by the middle of the following week and it was always a

total hit. We were living on this ranch up in Eastern Oregon.

Helnwein Which comic strip inspired you the most?

Barks: I have been asked this question many times. There were at

least a dozen.

Helnwein: Popeye the Sailor?

Barks: One of them could have been Popeye the Sailor. I didn't

care much for the drawings, but I loved the stories - they were

very funny.

Helnwein: . . . and strange.

Barks: Yes, the construction of the stories, the way the gags

were phrased and the way these absurd characters would be

introduced. - Fascinating (laughs). But I guess, generally, I was

more influenced by drawings - I liked the art. I was more

inspired by that than stories or gags. So I was quite a collector

of comic strips that had good artwork in them. Like Prince

Valiant.

Helnwein: By Hal Foster.

Barks: Yes, and Flash Gordon by Alex Raymond. There was no humour

in their stuff and their stories were really awful, but I could

just sit there and look at the drawings and be inspired. Of

course I couldn't use those drawings very much in doing the duck

stories later on, except for the background, or the atmosphere of

the places. That helped to make those duck stories popular

because they appeared to be going to real places.

Helnwein: What was the first story

you wrote yourself?

Barks: This one here... (Barks refers to WDCS034 but in fact it

was WDCS032 - Editor's remark). That was in spring of 1943. In

those days it was ok to draw these black ducks. Today nobody

would dare to do that, because it would be insulting to African

Americans.

Helnwein: Well, I like those black ducks.

Barks: But look at this duck with the earrings; that would be

totally impossible today.

Helnwein: Outside of Donald were

there any other Disney characters you liked?

Barks: There was one I couldn't stand: it was Disney's Goofy.

Helnwein: Why?

Barks: Goofy was simply a half-wit. I could never understand what

was supposed to be funny about a half-wit. I liked Mickey for his

purposes. He was good in adventure-strips. But the thought of

having to draw something like this did not appeal to me. I

enjoyed working with the duck because I could knock him around,

have him get hurt - I could let him fall off cliffs. It was lots

of fun with Donald. With Mickey it would have been kind of

dangerous, because Mickey always had to be right. With the duck I

had a comedian that I could treat badly and who I could make fun

of.

Helnwein: Donald was the looser type.

Barks: That's right, he was a kind of looser.

Helnwein: But one with whom one could identify and whom one could

love.

Barks: There were many other characters in Disney, but I cannot

remember a single one who has survived.

Helnwein: What about Pegleg Pete?

Barks: Yes, he was a great scoundrel. But they also had Jose

Carioca for a while, a parrot who came out of the Saludos Amigos

animated movie. I don't think he ever became very popular with

the people, because he was such an over-baring, little snob -

such a know-it-all snob. Pluto was in a lot of their comic-strips,

but he was a very artificial dog, so different from any idea one

might have of a dog. I never liked him very much. He was a dumb

dog, you might say. No, when I think of all the characters Disney

ever had, Donald was the best.

Helnwein: But before you took him on, he didn't have much of a

personality. Only in your stories did he become a real human

being.

Barks: It seems that way. If you have a story to tell, a story

that somebody is going to read over and over again, you have to

put some substance into it. It takes more than just a bunch of

pratfalls and bumps on the head. There had to be motivation for

the different things the characters did, and revenge for their

mistakes (laughs). It took a lot to write a ten-page story. A lot

of the guys didn't take the time to go into it that far and as a

result there were a lot of the comic book stories that never

lasted for very long. With my stories, because I worked so hard

to make the story plausible and give it a reason for having been

written, people would read it over and over again. They didn't

throw the comic book away. So these stories are still alive

today, while many others are gone and forgotten.

Helnwein: Did you have contacts to

any other comics artists?

Barks: Very few. I remember one who was pretty successful in his

work for Western Publishing. He told me I was foolish to put so

much work into my duck stories. He had just started to work for a

New York publisher who was putting out some stories about a

couple of crows. And he said, Oh, you can get twice as much

per page than you're getting from Western Publishing. But I

just couldn't see myself writing for those bunch of crows. I

didn't like their style or their reason for being there. They

were just a couple of pushy jerks, and I saw no chance to invent

stories which had no substance or any kind of dramatic

development for that. Well, I said, I'd rather keep

on like I am, on peanut wages, but getting some personal

satisfaction out of the stories that I write.

Helnwein: Over the years you have

fully developed Duckburg with all its different personalities.

Barks: Oh, yeah, that just evolved out of the fact that I had to

keep getting some material to create new interest in each story I

wrote ... expanding little by little, making more of the city of

Duckburg - the places where these events took place and a little

more about the people that Donald had to contact and do business

with. The whole family just gradually grew - and so did Duckburg.

Helnwein: It's funny, but I and many others of my generation have

learned a lot from these stories, because they always contained

some real information. Seriously - I've learned more from Donald

Duck than I have in all the schools I went to.

Barks: Well, I don't know exactly why I did so much research for

my stories, but I had the feeling the ducks had to act in real

places, otherwise the stories would look silly. I know in the

other duck stories in comics they went to islands like Booga

Booga or something like that - places that didn't have any

relation to reality. And they made their drawings in little

squiggly backgrounds, which didn't have the right character of,

for example, the South Seas. When I sent my ducks to the South

Seas, I gave it a name that sounded very much like it could

actually be on a map. And I would go and look at pictures of

plants and trees there, and islands and the mountains and all the

rest. I made my background look like the ducks went to just such

a place.

Helnwein: At one point you became

a little too realistic - do you remember the story about this

chemical formula, which existed in reality, but which was a top

military secret of the US?

Barks: Well, I'll tell you - I just stole that out of the

Encyclopedia Britannica. It was a big article on chemistry with

all different chemical formulas, and it was written in this

gibberish - CO H and so on - and I just looked at a whole string

of those things and looked at about the middle of that. And I

thought, Well, may be it's harmless enough if I just take these

bunch of chemicals and sort of jumble them up and stick them on a

piece of paper. Well, that is what I did, and it turned out that

it was a powerful chemical formula.

Helnwein: You are one of the few

people after whom a planet was named.

Barks: It was an asteroid. In one of my later stories, called

Island in the Sky, sometime in the sixties, the ducks try to find

a place to hide Uncle Scrooge's money, and they passed a bunch of

these small asteroids on the way there. One of the scientists at

Cornell University, where they had a whole laboratory for study

of the asteroids, read that comic book and thought that was quite

a thing, that these ducks could run onto a bunch of peculiar

asteroids on their way to the asteroid belt. Anyway, they thought

that was pretty good. My stories made the asteroids interesting,

and opened up a possibility that there might even be some amongst

them that would have a few vegetables growing on them. - And so

they named one of their discoveries after me: 2730 Barks. He

wrote to tell me that the surface was approximately 100 hectares

(approx. 250 acres) in size.

Helnwein: Well, you have a place to go when this world is

destroyed.

Barks: In any case it would be big enough for a money bin.

Helnwein: Did you know Disney

personally?

Barks: Oh yes, I went to story meetings with Walt. He was the guy

who'd come in at the last session, and a couple of the times he

also joined the production of one of these stories.

Helnwein: How was it to work with him? There are people who claim

that he was a dictator.

Barks: If you had a really good story, he was a pleasant guy to

have in the room - he would laugh and contribute more gags. But

if the story wasn't good he was very critical. Well, he had to be.

After all, it was his money that was paying us our wages, so if

the story wasn't good he would let us know. But generally we were

very careful to have the story in pretty good shape before we

ever showed it to him.

Helnwein: Was he really competent?

Barks: Oh yes - he knew exactly when a gag was going to fall flat.

He would tell you that it needs more work or it needs to be

shortened.

Helnwein: Did he also care about the drawing or was he more

interested in the gag?

Barks: He was pretty indifferent to the drawings in the story

department; they only had to carry the story. If we had made

sharp, detailed drawings, he would certainly have been upset. He

would have told us: I'm paying you guys to think of ideas and

stories and to get something moving.

Helnwein: You just showed me an

old sketch, which you made during a union meeting. There are

different caricatures of people, who are pointing at a figure of

Hitler; what does that mean?

Barks: That was after work in one of the buildings in Hollywood.

After the Disney strike we founded a union, and this was supposed

to be a union meeting. But instead of talking about salaries and

working conditions there were a bunch of war agitators, who

advocated that America should declare war on Germany and who

wanted to send our boys into battle. Most of us didn't like it at

all that America entered the war. Why for heaven's sake? We had

already been over there once and had fought the Germans in 1916-1917,

and supposedly this was to bring about peace for the whole world

and for all time. And now we were at it again, sending our boys

to death. For most of us at the Studio it looked like the

repetition of a senseless tragedy. Besides we were disturbed by

the fact that Melvin Douglas, a notorious communist,

told us this. He said we had to go to war in order to save Russia

from the Nazis who were standing at the gates of Stalingrad. But

we didn't give a damn which side won as long as we could stay out

of it.

Helnwein: Was Disney present at these meetings?

Barks: No, none of the leading Disney employees were there. It

was a labor union, after all.

Helnwein: Where you there when the

great strike took place?

Barks: Well, I was in the story department; we didn't strike. The

animators and in-betweeners were the ones on strike. We in the

story department went through the picket line every morning.

Helnwein: What was your view of the strike?

Barks: I was against it. I had the feeling that something was

being destroyed. The Disney studios were a place where there were

no time clocks - we were able to come to work whenever we wanted

to. If you went to work, did a good job and had something to show

for your efforts, you got paid damn well. If you were shirking

and complaining all the time you didn't get a raise, and it was

these shirkers and complainers who had organized this strike.

Helnwein: Do you think that Disney was fair to his employees and

artists?

Barks: He was fair - of course, he could have been more

considerate and humane to his employees, but those were hard

times. He brought a bunch of us, who, if we were lucky, could

earn ten dollars a week doing whatever job - and he gave us

twenty. I know many who were not grateful to him for that. They

thought that if a Disney film brings in $100, 000, they should

get half of it. But Walt invested the entire amount in order to

make a new film.

Helnwein: Did Disney ever comment

on your Donald Duck stories?

Barks: I don't even know whether or not he ever read my stories.

It was the people from the Publication Department who took care

of these things and who represented Disney's interests regarding

the comic books. They knew what I did and the fact that they

didn't lose their jobs and were there the whole time and well

paid, points to the fact that Disney must have been satisfied.

Helnwein: Did you learn about all

the places you describe in your stories just from National

Geographic magazines?

Barks: They were my most important sources of information

regarding geography, nations, people and places.

Helnwein: Did you ever go to any of these places?

Barks: No. I was in Tijuana, Mexico, and in Victoria, British

Columbia, that's all.

Helnwein: Do you remember, when

you drew the first duck in your life?

Barks: I think in grammar school, I scribbled one into a notebook.

I drew the first Donald in 1935, when I came to Disney.

Helnwein: Was there censorship at

Disney?

Barks: Yes.

Helnwein: Was your work ever censored?

Barks: Not often, I already had seven years experience working in

animation and I knew what they wanted and didn't want.

Helnwein: I am thinking of the espionage story with all the spies

and counter-spies and counter-counter-spies, where you drew

beautiful human girls: with real breasts.

Barks: That one got me into trouble. The first problem happened

with my 2nd or 3rd story. It was a ten-page story, Donald was a

life-guard, and there was this sweet, well-endowed duck girl. I

had to spend several hours in the art editor's office in order to

flatten all the breasts.

Helnwein: Would you have liked to

write more erotic stories with attractive girls, if it had been

allowed?

Barks: Oh yes, I would have liked that. There wouldn't have to be

more sex, necessarily, but I would have used attractive looking

human girls. But the editors rejected this. They didn't want to

let the ducks blend with real humans under any circumstances. The

girls had to have duck or dog faces. About the same time when

these stories were put together, Walt Disney brought out the

animation film Saludos Amigos in which Donald acted like a real

wolf.

Helnwein: Like a wolf?

Barks: Yes, he strutted and flirted and ran after all the

beautiful girls like a lascivious wolf. It made me think that I

might be able to get my story through.

Helnwein: When you had retired,

you began to paint in oil. But you were not allowed to paint your

ducks, since the copyright belonged to Disney, didn't it?

Barks: Yes, for five years I painted and drew little landscapes

and sold them at exhibitions. Those were meager years, I didn't

earn much. I think it was in 1971, when someone asked me if I

could paint him a picture of the cover with the little old

sailboat from the year 1949. Well, I said these ducks belong to

Disney and I would have to ask permission. But I thought it would

be a pleasant way to earn a few dollars, because I had no luck

with my other pictures. So I wrote to George Sherman, who at that

point managed the Publications Department, and he simply said: of

course - go to it! He added that the pictures would have to

be good enough, so as not to cause the Disney Studios any

embarrassment. In 1976 I stopped painting, because, in the

meantime, the collectors had become very pushy. When I painted a

picture for someone, all the others were mad at me, because

everyone thought it should have been for him. It had become

impossible to keep the waiting list under control.

I had no idea how to satisfy all these people, and besides, I

didn't want to paint any more ducks.

Helnwein: But later you reversed yourself.

Barks: Between 1976 and 1982 I had peace and quiet. Then I

started with the lithographs and new oil paintings. But now I

have reached a point, where I don't want to work any longer. I

believe I'll never paint another duck.

Helnwein: You have drawn millions of them.

Barks: Yes, that many for sure.

|

|

This contribution originally appeared at Gottfried Helnwein's website. © Gottfried Helnwein

| http://www.cbarks.dk/THEMEETINGShelnwein.htm | Date 2003-02-24 |